When you take a medication like levothyroxine or tacrolimus, you’re not just taking a chemical-you’re trusting that every pill, every dose, every bottle gives you the exact same result. But what happens when your pharmacy switches the brand? Or your insurance changes the generic? For most drugs, it’s no big deal. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even tiny differences can matter-sometimes dangerously so.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI drugs sit on a razor’s edge. The difference between a dose that works and one that harms is slim. Take warfarin, for example. Too little, and you risk a blood clot. Too much, and you could bleed internally. Its therapeutic index is just 2 to 4-meaning the toxic dose is only 2 to 4 times higher than the effective dose. Compare that to an antibiotic like amoxicillin, where the gap between safe and harmful is hundreds of times wider.

The FDA doesn’t publish a full list, but it’s clear on which drugs fall into this category: digoxin, lithium carbonate, phenytoin, carbamazepine, cyclosporine, theophylline, and tacrolimus. These aren’t random meds-they’re used for life-threatening or chronic conditions: heart failure, epilepsy, organ transplants, bipolar disorder. One misstep, and the consequences can be severe.

Why Generic Switching Gets Complicated

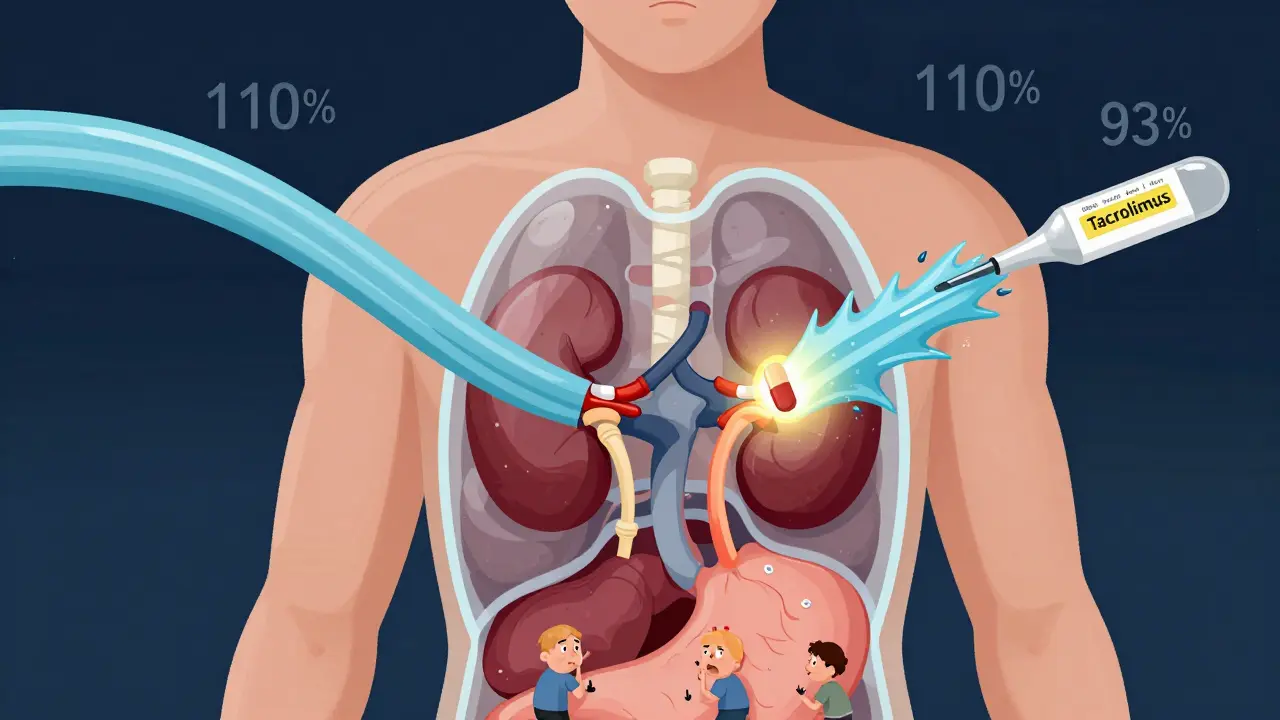

Generic drugs are required to be bioequivalent to the brand. That means they must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream within a certain range-usually 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. But for NTI drugs, the FDA tightens that range to 90% to 111%, sometimes even 95% to 105%. That sounds strict, right? It is. But here’s the catch: bioequivalence is measured in averages across a group of healthy volunteers. It doesn’t guarantee that every single patient will react the same way.

Take tacrolimus, used after kidney transplants. A 2015 study found that when patients switched between generic versions, their blood levels varied by 21.9% on average. That’s not a small fluctuation-it’s enough to trigger organ rejection. One manufacturer’s capsule might deliver 93% of the active ingredient, another’s 110%. Neither is outside the FDA’s legal limits. But for a transplant patient, that 17% swing between two generics could mean the difference between survival and failure.

Real-World Data: What Happens When You Switch?

Some studies say switching is fine. Others say it’s risky. The truth? It depends on the drug and the person.

For levothyroxine, a 2021 FDA analysis of over 10,000 patients showed no meaningful difference in TSH levels between brand-name Synthroid and generic versions. The average difference? Just 0.03 mIU/L. That’s clinically insignificant. Many patients switch generics without issue.

But look at phenytoin, used for seizures. A 2022 review in PMC found that even when bioequivalence studies showed no statistical difference, neurologists still reported breakthrough seizures after generic switches. Why? Because in epilepsy, a 10% drop in blood levels might be enough to trigger a seizure. And one patient’s body might absorb a different generic formulation differently than another’s.

And it’s not just about the active ingredient. Fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes vary between companies. A change in how a tablet dissolves in your stomach can alter how fast the drug enters your bloodstream. For NTI drugs, timing matters.

What Do Pharmacists and Doctors Think?

There’s a gap between science and practice.

A 2019 national survey found that 87% of pharmacists believe generic NTI drugs are just as effective as brand-name. But 63% of them also said they’d received complaints from patients or doctors after switching. That’s not a contradiction-it’s a warning. Pharmacists know the science says it’s safe. But they’ve also heard the stories: the patient who lost weight after switching levothyroxine, the transplant recipient whose creatinine spiked, the person who had a seizure after a pharmacy change.

Doctors are even more cautious. The American Academy of Neurology explicitly advises against automatic substitution of antiepileptic NTI drugs. The Epilepsy Foundation has collected dozens of anecdotal reports of seizure recurrence after switching generics. These aren’t outliers-they’re signals that population-level data doesn’t capture individual biology.

State Laws and the Patchwork of Rules

In 27 U.S. states, laws restrict or ban automatic substitution of NTI drugs without the prescriber’s approval. In others, pharmacists can switch generics freely unless the doctor writes “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Necessary.”

That means your experience depends on where you live. In California, you might get the same generic every time. In Texas, your pharmacist might switch you to a cheaper version without telling you. And if you’re on Medicare or Medicaid, cost-saving policies often push you toward the lowest-priced generic-even if it’s not the one your doctor originally prescribed.

What Should You Do?

If you’re taking an NTI drug, here’s what actually works:

- Ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Necessary” on your prescription. It’s legal. It’s your right.

- Know your generic. Check the pill’s imprint code or ask your pharmacist for the manufacturer’s name. Write it down. If it changes, ask why.

- Monitor your levels. If you’re on warfarin, check your INR more frequently after a switch. If you’re on lithium or tacrolimus, ask for a blood test within 2-4 weeks after switching.

- Speak up. If you feel different-more tired, more anxious, more seizures, more tremors-don’t assume it’s “just stress.” Tell your doctor. Track your symptoms. Bring your pill bottles to appointments.

And if you’re switching from brand to generic, or between generics, give your body time. Don’t expect immediate results. But don’t ignore warning signs either.

The Bigger Picture

The FDA insists generic NTI drugs are therapeutically equivalent. And for most people, they are. But the system is built on averages. Real people aren’t averages. They’re individuals with different metabolisms, gut health, kidney function, and genetic profiles.

Brand-name manufacturers change their formulas too. And no one screams about that. But if a generic changes, suddenly it’s a crisis. That’s not fair. It’s also not entirely logical.

The real issue isn’t generics. It’s the lack of consistent monitoring and communication. We assume a pill is a pill. But for NTI drugs, that’s not true. And until we treat them like the high-risk medications they are-by tracking, documenting, and personalizing-we’re leaving patients vulnerable.

There’s no perfect solution. But awareness is the first step. If you’re on one of these drugs, don’t let cost or convenience override safety. Your life might depend on knowing which pill you’re taking-and why.

Are all generic drugs the same, even for NTI medications?

No. While all generics must meet FDA bioequivalence standards, they can differ in inactive ingredients, manufacturing processes, and how quickly they dissolve. For NTI drugs, even small differences in absorption can affect blood levels enough to cause side effects or reduce effectiveness. Two generics of the same drug may not behave the same way in your body.

Can I ask my pharmacist not to switch my NTI drug?

Yes. You have the right to request the brand-name version or a specific generic manufacturer. Ask your doctor to write "Dispense as Written" on your prescription. If your insurance denies coverage, you can appeal or pay a small difference out-of-pocket. Many patients do this for levothyroxine, tacrolimus, or warfarin without issue.

How do I know if my generic has changed?

Check the pill’s imprint code (letters or numbers printed on it) or the manufacturer’s name on the bottle. If it’s different from your last fill, ask your pharmacist. You can also look up the National Drug Code (NDC) on the FDA’s website. If you notice new side effects or changes in how you feel after a refill, a switch may be the cause.

Why do some doctors refuse to prescribe generic NTI drugs?

Some doctors, especially neurologists and transplant specialists, have seen patients experience adverse events after switching generics-even when studies say it’s safe. They prioritize individual outcomes over population data. For patients with epilepsy, organ transplants, or severe heart conditions, the risk of a bad reaction isn’t worth the savings. Their caution is based on real clinical experience, not just theory.

Is it safe to switch between generic manufacturers of levothyroxine?

For most people, yes. A 2021 FDA study found no significant difference in TSH levels between brand-name and generic levothyroxine. But some patients-especially those with thyroid cancer or severe hypothyroidism-do report symptoms after switching. If you feel different after a refill, get your TSH checked. Don’t assume it’s all in your head.

What to Watch For After a Switch

After switching NTI drug manufacturers, keep an eye out for these signs:

- Unexplained fatigue, weight gain, or mood changes (levothyroxine, lithium)

- Increased tremors, confusion, or nausea (tacrolimus, cyclosporine)

- Breakthrough seizures or increased seizure frequency (phenytoin, carbamazepine)

- Unusual bruising, bleeding, or dark stools (warfarin)

- High creatinine or low urine output (tacrolimus, cyclosporine)

If any of these happen, contact your doctor. Don’t wait. A simple blood test can tell you if your drug levels have shifted. And if they have, you can switch back-or your doctor can adjust your dose.

The Bottom Line

Generic NTI drugs aren’t inherently dangerous. But they’re not interchangeable in the way other generics are. They require more attention, more monitoring, and more communication. The system is designed to save money. But for these drugs, safety should come before cost. If you’re taking one, be your own advocate. Know your drug. Know your dose. Know your manufacturer. And never hesitate to ask questions.

11 Comments

Man, I’ve been on tacrolimus for 8 years post-kidney transplant. Switched generics twice and both times my levels spiked. Had to go to the ER once. Now my doc writes "Dispense as Written" and I pay the extra $15. Worth it. Don’t gamble with this stuff.

i just found out my levothyroxine switched brands last month and i’ve been so tired lately… i thought it was stress or my new job. i’m calling my dr tomorrow to get my tsh checked. thanks for this post, seriously.

For real, this is one of those areas where the FDA’s one-size-fits-all approach fails. Bioequivalence studies use healthy volunteers. But people on NTI drugs? They’re often elderly, have kidney issues, or are on 5 other meds. Their absorption isn’t textbook. That 90-111% range? Doesn’t mean squat when your body’s not in perfect health.

I’ve seen patients on carbamazepine go from stable to seizing after a pharmacy switch. No one’s at fault. Just a system that treats pills like widgets.

Doctors need to be proactive. Pharmacies need to notify. Patients need to track. We’re all failing each other here.

Oh please. This is just fearmongering. The FDA has over 50 years of data showing generics are safe. If you can’t handle a $5 savings, maybe you shouldn’t be on medication at all. People complain about their meds changing like it’s a personal betrayal. Grow up.

Also, if you’re having side effects, maybe your thyroid is just being dramatic. Or you’re eating too much soy. I’ve read the studies. You haven’t.

THEY’RE PLAYING WITH OUR LIVES. YOU KNOW WHO MAKES THE MOST MONEY OFF THIS? THE PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES WHO OWN THE BRANDS AND THE GENERIC MANUFACTURERS. THEY’RE THE SAME PEOPLE. THEY WANT YOU SWITCHING. THEY WANT YOU CONFUSED. THEY WANT YOU TOO TIRED TO FIGHT.

My cousin went into a coma after a generic switch. He was on phenytoin. They didn’t even tell his family. Now he’s in a nursing home. And the pharmacy? Got a bonus for cutting costs.

This isn’t science. This is capitalism with a stethoscope.

It’s not about generics being bad. It’s about how we treat human beings like data points. We don’t say "this patient has a 92% chance of absorbing this drug"-we say "this drug is safe for everyone." But we’re not averages. We’re not test tubes. We’re broken, beautiful, weirdly individual bodies trying to survive in a system that treats us like inventory.

If your doctor won’t write "Dispense as Written," find a new one. If your pharmacist won’t tell you when it changes, find a new pharmacy. You are not a cost center. You are not a statistic. You are someone’s child, someone’s friend, someone who deserves to feel like themselves.

my pharmacist switched my cyclosporine last week without telling me. i noticed my hands shaking and my blood pressure was all over the place. called the dr. they checked my levels. 22% off from before. switched back. no more generic for me. never ask again.

Look, I get it. You’re scared. I’m a pharmacist in Mumbai and I’ve seen this play out with antiepileptics and immunosuppressants in low-income settings where patients are forced to switch because they can’t afford the brand. But here’s the thing: the real tragedy isn’t the generic. It’s the lack of access to consistent monitoring. In the U.S., you have labs, you have doctors, you have insurance. In places like mine? A patient might go three months without a blood test. That’s the real crisis. The generic? It’s just the symptom.

So yes, advocate for yourself. But don’t forget to advocate for the global system that leaves millions without even the option to choose.

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been on lithium for 12 years. I switched generics last year and didn’t realize it until I found the bottle label. I felt like a different person-numb, slow, like my thoughts were underwater. I didn’t say anything for weeks because I thought I was just "getting old."

When I finally asked, my doctor said "it’s probably fine." I went to another clinic. They ran the test. My level was 0.4 below therapeutic. I cried in the parking lot.

Don’t wait. Check your bottle. Ask. Track. You’re not being dramatic. You’re being smart.

While the concerns raised regarding bioequivalence variability in NTI medications are empirically valid and clinically significant, it is imperative to acknowledge the regulatory framework’s foundational intent: to ensure broad accessibility to life-sustaining therapeutics at reduced cost. The challenge lies not in the pharmacological equivalence per se, but in the absence of standardized, patient-centered tracking protocols across prescriber, pharmacy, and payer systems. A mandatory, digitally integrated medication history log-linked to the NDC and patient-reported outcomes-would mitigate risk without compromising cost-efficiency. This is not an argument against generics. It is a call for intelligent, humane implementation.

Let me guess-the FDA is in cahoots with Big Pharma. The "90-111%" range? A joke. The real bioequivalence is 0% when you consider the fillers. They use talc from China. The coating? Made with corn syrup from Monsanto. Your body doesn’t know the difference between the active ingredient? That’s what they want you to believe.

I’ve studied the patents. The same company that makes Synthroid owns three of the top four generic brands. The FDA doesn’t test for absorption variability in real patients. They test in healthy 22-year-olds on a treadmill. And you think that’s science?

This is why your thyroid is broken. This is why your transplant is failing. They’re poisoning you slowly. And they call it "cost-saving."