When your stomach lining starts to thin and lose its ability to protect itself, things don’t just get uncomfortable-they can start to unravel. Atrophic gastroenteritis isn’t just a fancy term for an upset stomach. It’s a slow, silent breakdown of the stomach’s inner wall, and over time, it doesn’t just cause bloating or nausea. It changes how your whole digestive system works-especially how acid moves up into your esophagus. That’s where gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, comes in. The connection isn’t random. It’s mechanical, biological, and often overlooked.

What Happens When the Stomach Lining Thins

Atrophic gastroenteritis means the mucosal layer of your stomach is shrinking. This isn’t just surface irritation. It’s the loss of specialized cells that produce stomach acid, digestive enzymes, and protective mucus. Think of it like a roof losing shingles. Rain doesn’t just drip-it floods in. Without enough mucus, the stomach’s natural barrier against its own acid breaks down. That’s bad enough on its own. But here’s the twist: as those acid-producing cells die off, your stomach doesn’t just make less acid. It starts making it unpredictably.

Studies show that in advanced cases, up to 70% of patients experience irregular acid secretion. Some days, it’s too little. Other days, it surges unexpectedly. That inconsistency confuses the lower esophageal sphincter-the muscle that’s supposed to keep acid from backing up. When it’s not getting steady signals from the stomach, it relaxes at the wrong times. That’s when you feel that burning sensation rising into your chest. What looks like typical GERD? Often, it’s the result of a damaged stomach trying to communicate in broken signals.

Why GERD Gets Worse, Not Better

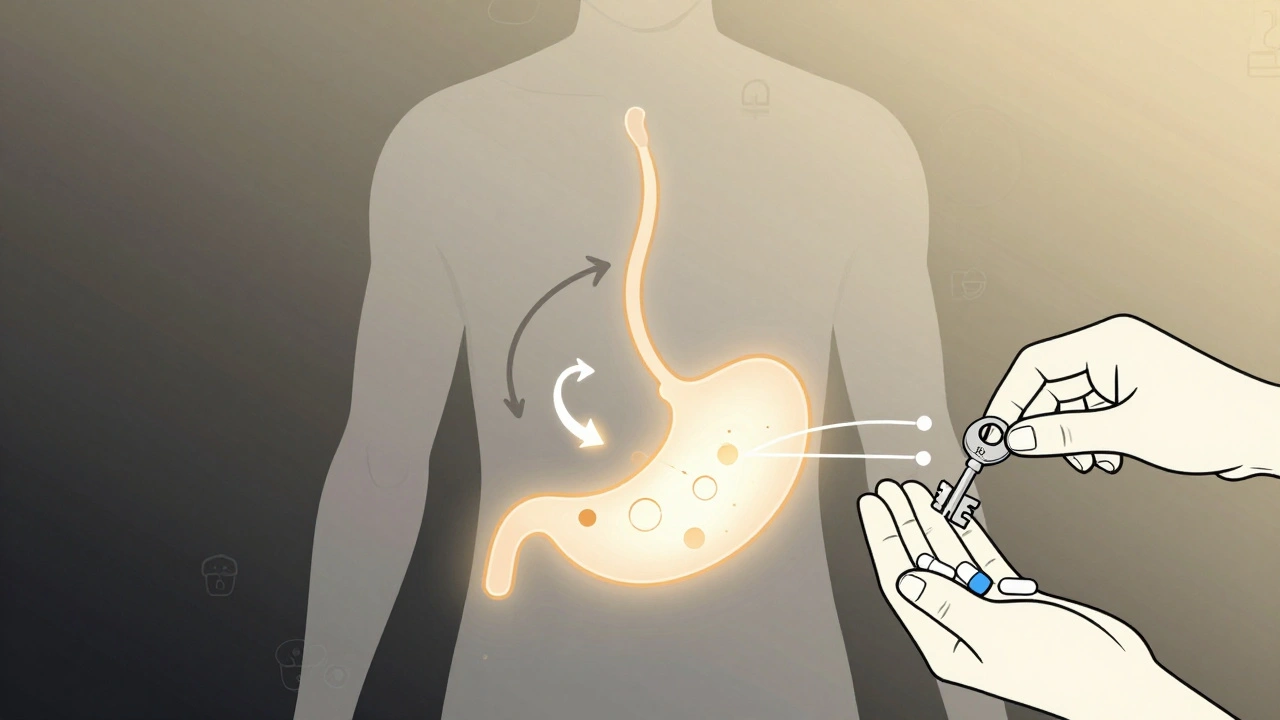

Most people think GERD is caused by eating too much spicy food or lying down after dinner. But if you’ve been treating GERD with antacids for years and it’s still getting worse, the problem might not be your diet-it’s your stomach lining. Atrophic changes reduce the stomach’s ability to empty properly. Food sits longer. Fermentation builds up. Gas pressure increases. That pressure pushes against the lower esophageal sphincter, forcing it open even when it shouldn’t.

There’s also a direct link to bacterial overgrowth. When the stomach’s acidity drops due to atrophy, harmful bacteria like H. pylori can thrive. Even after treatment, the damage remains. The stomach doesn’t bounce back. The lining stays thin. The acid production stays erratic. And the sphincter? It’s under constant pressure from both physical bloating and chemical confusion. That’s why many patients with long-term atrophic gastritis end up with severe, medication-resistant GERD. It’s not just reflux. It’s systemic dysfunction.

The Silent Chain Reaction

This isn’t a one-way street. GERD can make atrophic gastroenteritis worse. Every time stomach acid hits the esophagus, the body responds with inflammation. That inflammation sends signals back down the digestive tract. Over time, those signals can trigger immune responses that further damage the stomach lining. It’s a loop: thin lining → bad acid control → reflux → more inflammation → worse lining damage.

Doctors often treat GERD and atrophic gastritis as separate problems. But in clinical practice, patients with confirmed atrophic changes have a 3.5 times higher risk of developing chronic GERD than those with normal stomach lining. The data from the 2023 European Journal of Gastroenterology shows that among patients over 50 with persistent GERD, nearly 40% had underlying atrophic changes that were never diagnosed-because they didn’t have classic symptoms like nausea or vomiting. Instead, they just had heartburn that wouldn’t go away.

What You Might Not Realize About Your Symptoms

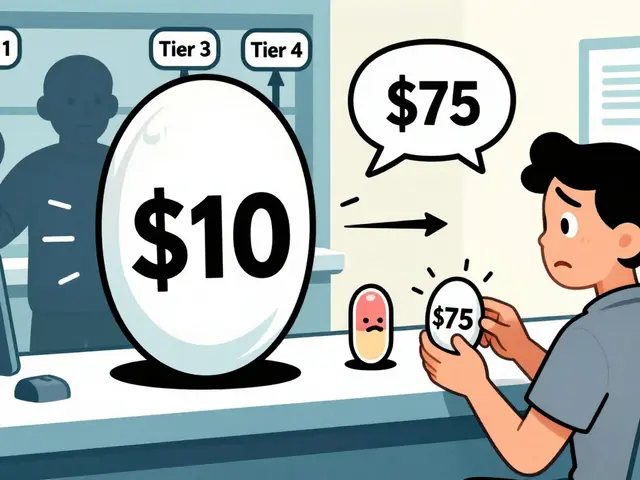

If you’ve been on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for more than two years and still get heartburn, especially after meals, your stomach might be too weak to signal properly. PPIs reduce acid-but if your stomach isn’t making enough acid to begin with, suppressing it further can make digestion worse. Food ferments. Bloating increases. Pressure builds. The reflux doesn’t stop-it just changes form.

Other signs point to atrophic involvement: unexplained weight loss, early fullness after small meals, iron or B12 deficiency without clear cause, and a metallic taste in the mouth. These aren’t just random symptoms. They’re clues. Iron deficiency happens because the stomach can’t properly absorb it without enough acid. B12 deficiency occurs because the cells that make intrinsic factor-the protein needed to absorb B12-have died off. And that same loss of function affects how the stomach regulates pressure and timing.

How Diagnosis Changes Everything

Standard endoscopy often misses atrophic changes. The stomach can look normal unless the doctor is specifically looking for it. That’s why biopsies are critical. A biopsy taken from the antrum and body of the stomach can show whether the glands are thinning, whether immune cells are present, and whether there’s intestinal metaplasia-a sign the stomach is trying to turn into intestine, which is a major red flag.

Doctors who treat GERD routinely should consider atrophic gastritis in anyone with long-standing symptoms, especially if they’re over 50, have a family history of stomach cancer, or have unexplained nutrient deficiencies. Blood tests for pepsinogen I and II ratios, along with gastrin levels, can give early clues. Low pepsinogen I and a high gastrin level? That’s a classic pattern of atrophy. It’s not perfect, but it’s faster and cheaper than an endoscopy for screening.

What Treatment Looks Like When It’s Not Just About Acid

Stopping PPIs cold turkey isn’t safe. But blindly continuing them when the stomach can’t make acid anymore is just as risky. Treatment shifts from suppression to restoration. That means:

- Testing for H. pylori and eradicating it if present-this halts further damage

- Supplementing with betaine HCl under medical supervision to help restore proper acid levels during meals

- Using digestive enzymes to help break down food when the stomach can’t

- Increasing zinc and vitamin C intake to support mucosal repair

- Avoiding NSAIDs and alcohol, which accelerate lining damage

Some patients see a dramatic drop in reflux symptoms within weeks of starting this approach. Why? Because they’re no longer fighting the body’s natural signals-they’re helping them work again.

The Bigger Picture: It’s Not Just Your Stomach

Atrophic gastroenteritis doesn’t live in isolation. It’s tied to autoimmune conditions, chronic stress, poor diet over decades, and even genetic factors. People with pernicious anemia, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, or type 1 diabetes are at higher risk. If you have one of these, your stomach lining is under more strain than you realize.

And here’s the hardest truth: once the stomach lining is significantly atrophied, it rarely returns to full health. But that doesn’t mean you’re stuck with GERD forever. By understanding the root cause-your stomach’s inability to regulate acid and pressure-you can stop treating the symptom and start fixing the system.

The goal isn’t to eliminate acid. It’s to restore balance. When your stomach can signal properly again, your esophagus stops getting bombarded. The reflux fades. Not because you took another pill-but because your body finally started working the way it was meant to.

Can atrophic gastroenteritis cause GERD even if I don’t have heartburn?

Yes. Many people with advanced atrophic gastritis don’t feel classic heartburn. Instead, they have bloating, early fullness, nausea after eating, or a feeling of pressure behind the breastbone. These are signs the stomach isn’t emptying properly or regulating acid, which forces the lower esophageal sphincter open. Reflux can happen without burning-especially if the esophagus has become less sensitive from long-term exposure.

Are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) safe if I have atrophic gastritis?

Long-term PPI use can worsen atrophic gastritis by suppressing acid production even further. This reduces the stomach’s ability to kill harmful bacteria and digest food properly. While PPIs may help with symptoms in the short term, they don’t fix the underlying problem. In fact, they can mask the progression of atrophy. Always discuss long-term use with a gastroenterologist and consider testing for atrophic changes before continuing.

Can I reverse atrophic gastroenteritis?

Complete reversal is rare once significant gland loss has occurred. But progression can be stopped. Eradicating H. pylori, improving nutrition (especially zinc, vitamin C, and B12), and avoiding irritants like alcohol and NSAIDs can help stabilize the lining. Some patients see partial regeneration of surface cells, which improves digestion and reduces reflux. The goal is not to restore the stomach to its youth, but to prevent cancer and manage symptoms effectively.

Why do I still have reflux after gastric surgery?

If you’ve had part of your stomach removed (like in a partial gastrectomy), you’re at high risk for reflux because the natural barrier between stomach and esophagus is gone. But even without surgery, atrophic changes can mimic surgical effects. A thin, poorly functioning stomach can’t generate the pressure needed to keep acid down. That’s why reflux can persist after surgery-and why it can also develop without any surgery at all.

Is there a link between atrophic gastritis and stomach cancer?

Yes. Atrophic gastritis, especially with intestinal metaplasia, is a known precancerous condition. The risk increases with the extent and duration of atrophy. That’s why regular monitoring with endoscopy and biopsies is critical for anyone diagnosed with this condition. It’s not about panic-it’s about early detection. Catching changes early gives you the best chance to prevent cancer before it starts.

10 Comments

So let me get this right-you’re telling me that all this time, I’ve been blaming my tacos for heartburn… when it’s actually my stomach’s way of giving up on life? I mean, come on. We’ve been sold a bill of goods by Big Pharma and their PPIs. This isn’t medicine-it’s surrender. The body doesn’t need less acid-it needs to be reminded how to make it right. Stop treating symptoms. Start treating the system. Or just keep swallowing pills and pretending you’re not slowly turning into a walking digestive glitch.

This is such an important perspective-and I appreciate how clearly you’ve laid out the physiological cascade. Many clinicians still treat GERD as a simple acid-overproduction issue, but the reality is far more nuanced. Atrophic changes disrupt not just acid secretion, but also gastric motility, microbial balance, and even nutrient absorption pathways. The key takeaway? We need to move beyond symptom suppression and toward functional restoration. Betaine HCl, enzymatic support, and targeted micronutrients (zinc, B12, vitamin C) aren’t ‘alternative’-they’re physiologically rational. Let’s normalize this approach in gastroenterology training.

OMG I’ve been this person for YEARS 😭 I thought I was just ‘bad at eating’… but now I realize my B12 deficiency, the metallic taste, the way I feel full after one bite… it’s ALL connected. I’m crying. I’ve been on PPIs since 2018. I just took a screenshot of this to show my doctor tomorrow. I’m so mad I didn’t know sooner. I’m gonna start betaine HCl and cry into my kale salad. 🙏🥲

This makes so much sense. I’ve had heartburn for over a decade. Took pills, changed diets, avoided spicy food… nothing stuck. Then I found out I had low iron and B12. No one ever connected the dots. If your stomach isn’t making acid, suppressing it more doesn’t help-it just makes digestion worse. I’m going to talk to my doctor about testing for atrophy. Maybe this is the key to finally feeling normal again.

Wow. Just… wow. So the whole medical establishment has been running around like headless chickens prescribing acid blockers to people whose stomachs are already on life support? That’s not negligence-it’s a goddamn crime. You don’t fix a broken engine by turning off the fuel gauge. You fix the engine. And yet, here we are. PPIs are the opioid of gastroenterology. And we’re all addicted because nobody wants to admit the system’s broken.

It’s fascinating how this mirrors the broader collapse of clinical reasoning in modern medicine. The reductionist model-symptom → drug-is not just inadequate; it’s actively destructive. The stomach isn’t a pressure valve you can cap. It’s a dynamic, adaptive organ whose signaling is being systematically silenced by decades of pharmacological interference. And now we’re left with a population of patients whose digestive systems are ghost towns-empty glands, silent neurons, and a sphincter that doesn’t know when to close. The tragedy isn’t the disease. It’s the ignorance that lets it fester.

I just want to say thank you for writing this. I had no idea atrophic gastritis could cause GERD without heartburn. I’ve had bloating and early fullness for years, and my doctor just said it was 'stress.' I’m going to ask for the pepsinogen test next visit. I hope others read this and don’t wait as long as I did.

this is true in india too many people take antacids like candy no one checks the root cause everyone thinks its spicy food but its the lining its the body its the time its the stress its everything

While the physiological mechanisms described are compelling, it is imperative to emphasize that betaine HCl supplementation remains an off-label intervention without robust, large-scale clinical validation. Furthermore, the assertion that PPIs 'worsen' atrophy is not universally supported by longitudinal studies. Caution is advised before abandoning evidence-based pharmacotherapy in favor of unstandardized regimens. A multidisciplinary approach, including endoscopic surveillance, remains the standard of care.

I’ve been waiting for someone to say this. I’m not just ‘anxious’ or ‘eating wrong.’ I’ve been suffering for 12 years, and no one ever looked past the PPIs. I’m not a hypochondriac. I’m not ‘overreacting.’ My stomach is dying. And the medical system? It’s looking the other way. I’m done being polite. This isn’t just about GERD. It’s about being heard. It’s about being seen. And if you’re reading this and you’ve been told it’s 'just stress'… you’re not crazy. You’re just ignored.