HIT Diagnostic Tool (4Ts Score Calculator)

How to Use This Tool

The 4Ts score helps assess the probability of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) by evaluating four key factors. Enter your values below to calculate the score.

Most people assume blood thinners like heparin are safe because they’re used so often - in hospitals, after surgery, even in routine IV lines. But there’s a hidden risk most patients never hear about: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or HIT. It’s rare, but when it happens, it can turn a life-saving drug into a life-threatening one. This isn’t just a lab anomaly - it’s a real, fast-moving danger that can cause blood clots, amputations, or even death if missed.

What Exactly Is HIT?

HIT isn’t just a low platelet count. It’s an immune reaction. When you get heparin - whether it’s a shot, an IV drip, or even a flush in your catheter - your body sometimes makes antibodies against a protein called PF4 that binds to heparin. These antibodies don’t just sit there. They latch onto your platelets, making them activate and clump up. That’s why your platelet count drops. But here’s the twist: while your platelets are being used up, your blood becomes hyper-clotting. You’re on a blood thinner, yet your body starts forming dangerous clots.

This isn’t theoretical. About half of people who develop HIT also develop clots - deep vein thrombosis in the leg, pulmonary embolism in the lungs, or even clots in the brain or abdomen. This combination of low platelets and clots is called HITT - heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. And it’s serious. Without treatment, 20-30% of people with HITT die.

When Does HIT Happen?

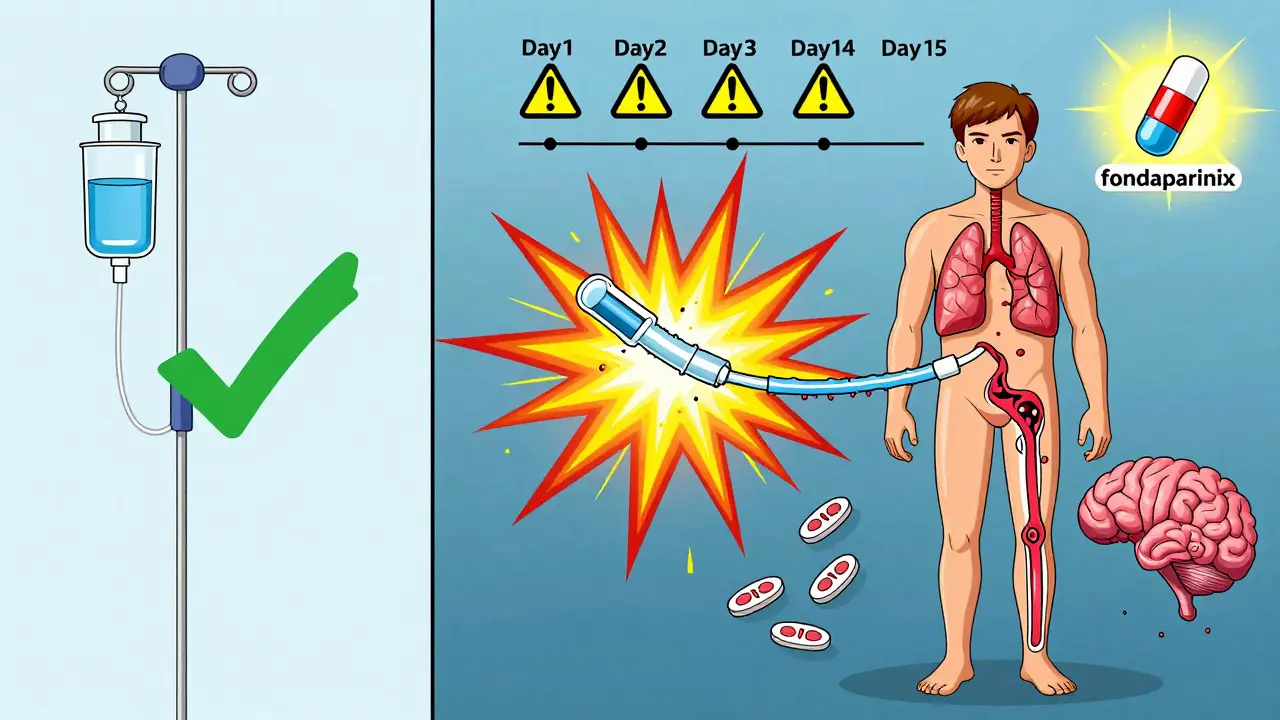

Timing matters. HIT doesn’t show up on day one. It usually appears between day 5 and day 14 after starting heparin. But if you’ve had heparin in the last 100 days - even just a few shots months ago - your body might already have the antibodies. In those cases, HIT can hit within 24 to 72 hours. That’s why a patient who had knee surgery six months ago and gets heparin again for a hospital stay can develop HIT almost immediately.

Unfractionated heparin - the older, more commonly used form - carries a 3-5% risk. Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin) is safer, but still risky at 1-2%. Orthopedic surgery patients are at the highest risk - up to 10% develop HIT after joint replacements. Women over 40 are also more likely to get it than men or younger people.

What Are the Warning Signs?

The symptoms aren’t subtle. If you’re on heparin and suddenly notice:

- Swelling, warmth, or pain in one leg - especially if it’s worse than expected after surgery

- Shortness of breath or sharp chest pain when breathing

- Unexplained bruising or dark, blackish patches of skin around where heparin was injected

- Fingers or toes turning blue or feeling cold

- Fever, dizziness, or sudden anxiety with no clear cause

These aren’t normal side effects. They’re red flags. Skin necrosis - tissue death at the injection site - is one of the clearest clinical signs. It’s rare, but when it happens, it’s almost always HIT. One patient in Alberta, after knee replacement, described waking up with a swollen calf and sudden chest pain. By the time she got to the ER, her platelets had dropped from 250,000 to 45,000. She had a pulmonary embolism.

How Is It Diagnosed?

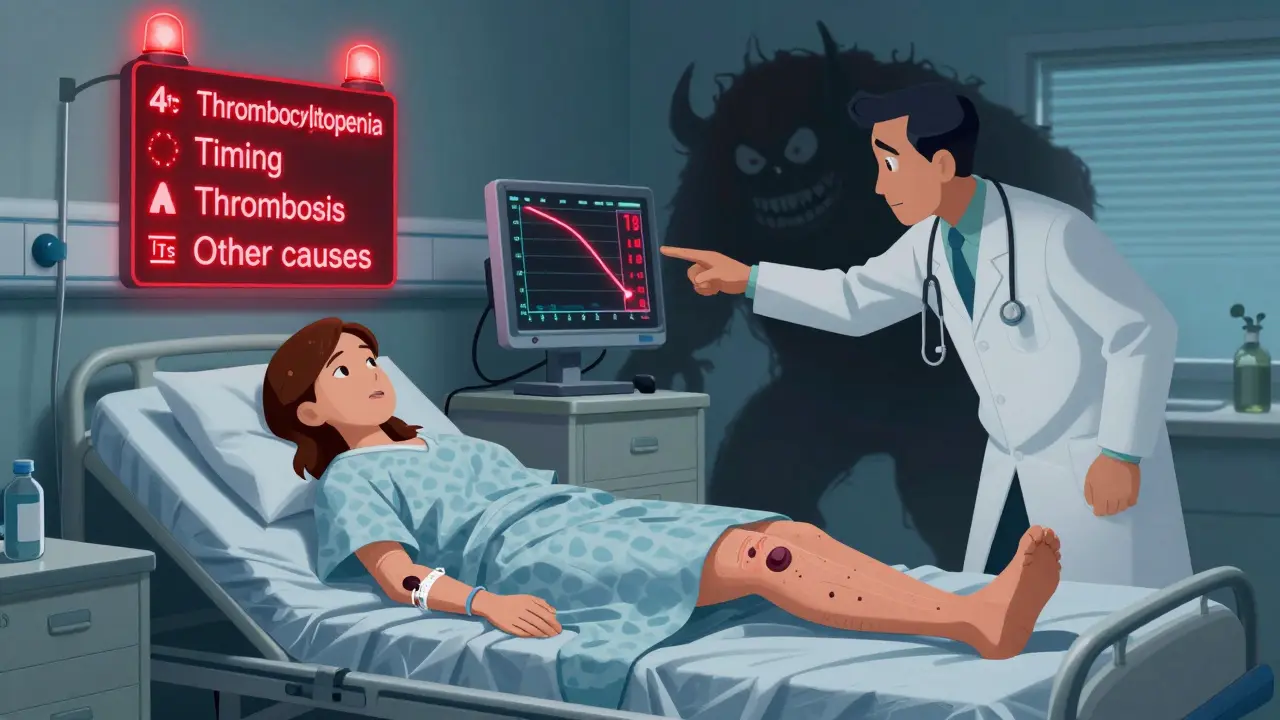

Doctors don’t just guess. They use a tool called the 4Ts score. It looks at four things:

- Thrombocytopenia - How much did your platelets drop? A drop of more than 50% counts as high risk.

- Timing - When did the drop happen? Day 5-14? High risk. Day 1? Probably not HIT.

- Thrombosis - Are there new clots? This bumps the score way up.

- Other causes - Is there another reason for low platelets? Like infection or drugs?

A score of 6-8 means high probability. 4-5 is intermediate. 0-3 is low. If your score is high, labs follow. First, an antibody test (ELISA). It’s sensitive - catches 95% of cases - but it can give false positives. That’s why the gold standard is the serotonin release assay. It’s harder to get, takes longer, but it’s 99% specific. If it’s positive, HIT is confirmed.

Here’s the catch: about 1 in 1,000 patients still get a false negative. So if your symptoms scream HIT and your test is negative, don’t ignore it. Trust the clinical picture.

What Happens If You Get HIT?

Stop heparin - immediately. All of it. That includes heparin-coated catheters, heparin flushes, even heparin locks in IV lines. Continuing heparin, even in small amounts, can make clots worse.

You need a different blood thinner - one that doesn’t touch PF4. The options:

- Argatroban - given by IV. Used if you have liver problems. Dose adjusted by blood tests.

- Bivalirudin - often used during heart surgery. Also IV.

- Fondaparinux - a once-daily shot. Newer guidelines now recommend this as first-line for non-life-threatening cases because it’s effective and easier to manage.

- Danaparoid - not available everywhere, but used in some countries.

Never start warfarin alone during HIT. It can cause skin necrosis - the same black patches you might see on your skin - and make things worse. Warfarin can be added later, but only after platelets recover above 150,000 and you’ve been on an alternative anticoagulant for at least five days.

Treatment lasts at least three months. If you had a clot, you’ll need six months or longer. Some people need lifelong anticoagulation if they’ve had multiple clots.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not random. The highest-risk groups:

- Patients after orthopedic surgery - especially hip or knee replacements

- Women over 40

- People who’ve had heparin in the past 100 days

- Those on unfractionated heparin for more than five days

- Patients in ICUs with central lines flushed with heparin

Even low-dose heparin - like the 10 units you get in a catheter flush - can trigger HIT. About 15-20% of HIT cases come from these tiny exposures. That’s why hospitals are now switching to saline flushes where possible.

What’s Being Done to Prevent It?

Guidelines now require platelet checks every 2-3 days from day 4 to day 14 for anyone on heparin longer than four days. That’s not optional - it’s standard of care. But many hospitals still miss it. One study found 10-15% of HIT cases were delayed because doctors kept giving heparin while waiting for test results.

There’s also progress in testing. New antibody tests that look only at PF4 without heparin are being developed. They could cut false positives from 15% to under 5%. And researchers are working on new anticoagulants that don’t interact with PF4 at all. Two are already in Phase II trials.

But the biggest barrier isn’t technology - it’s awareness. Many clinicians still think HIT is too rare to worry about. It’s not. In the U.S. alone, 1-2 million people get heparin each year. That’s 50,000 to 100,000 potential HIT cases annually. And HITT cases cost hospitals $35,000-$50,000 extra per patient - not just in care, but in longer stays, rehab, and disability.

What Should You Do If You’re on Heparin?

If you’re on heparin - whether you’re in the hospital or getting shots at home - know the signs. If your platelets drop suddenly, or you develop new pain, swelling, or skin changes, speak up. Don’t assume it’s just normal recovery. Ask: Could this be HIT?

If you’ve had HIT before, you must tell every doctor, dentist, or nurse before any procedure. You’ll need to avoid heparin for life. There’s no cure for the antibodies - they stick around forever. And you’ll need alternative anticoagulants for any future clotting risk.

Most people recover fully if HIT is caught early. But if it’s missed, the consequences are permanent - amputations, chronic lung damage, strokes. It’s not a risk you can ignore. It’s a condition that demands vigilance - from patients and providers alike.

Final Thought

Heparin is one of the most common drugs in medicine. But HIT reminds us that even the most routine treatments carry hidden dangers. It’s not about avoiding heparin - it’s about knowing when to suspect it, test for it, and act fast. The difference between catching it on day 7 versus day 12 can be life or death.

Can you get HIT from a heparin flush in an IV line?

Yes. Even small amounts of heparin - like the 10-20 units used to flush a catheter - can trigger HIT. About 15-20% of HIT cases come from these low-dose exposures. That’s why many hospitals now use saline flushes instead, especially for patients who’ve had heparin before.

Is HIT the same as DIC?

No. DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation) is a different condition where widespread clotting and bleeding happen due to severe infection, trauma, or cancer. HIT is specific to heparin exposure and involves antibodies against PF4. Platelets drop in both, but in HIT, you get clots - not bleeding. DIC causes bleeding; HIT causes clots.

Can HIT happen after stopping heparin?

Yes. HIT can develop up to 30 days after stopping heparin, though it’s rare. The antibodies can linger and activate platelets even after heparin is gone. That’s why platelet counts are monitored for at least a month after stopping heparin in high-risk patients.

If I had HIT once, can I ever use heparin again?

No. Once you’ve had HIT, your body keeps the antibodies for life. Even tiny amounts of heparin - like in a surgical flush - can trigger a severe reaction. You must avoid all heparin products forever. Alternative anticoagulants like fondaparinux, argatroban, or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are used instead.

Does HIT go away on its own?

Type I HIT - the mild, non-immune kind - does resolve on its own within a few days. But Type II HIT, the dangerous immune-mediated form, does not. It requires immediate treatment. Left untreated, it leads to life-threatening clots. Never assume HIT will clear up by itself.

Write a comment